Human Brains. Interview with Udo Kittelmann

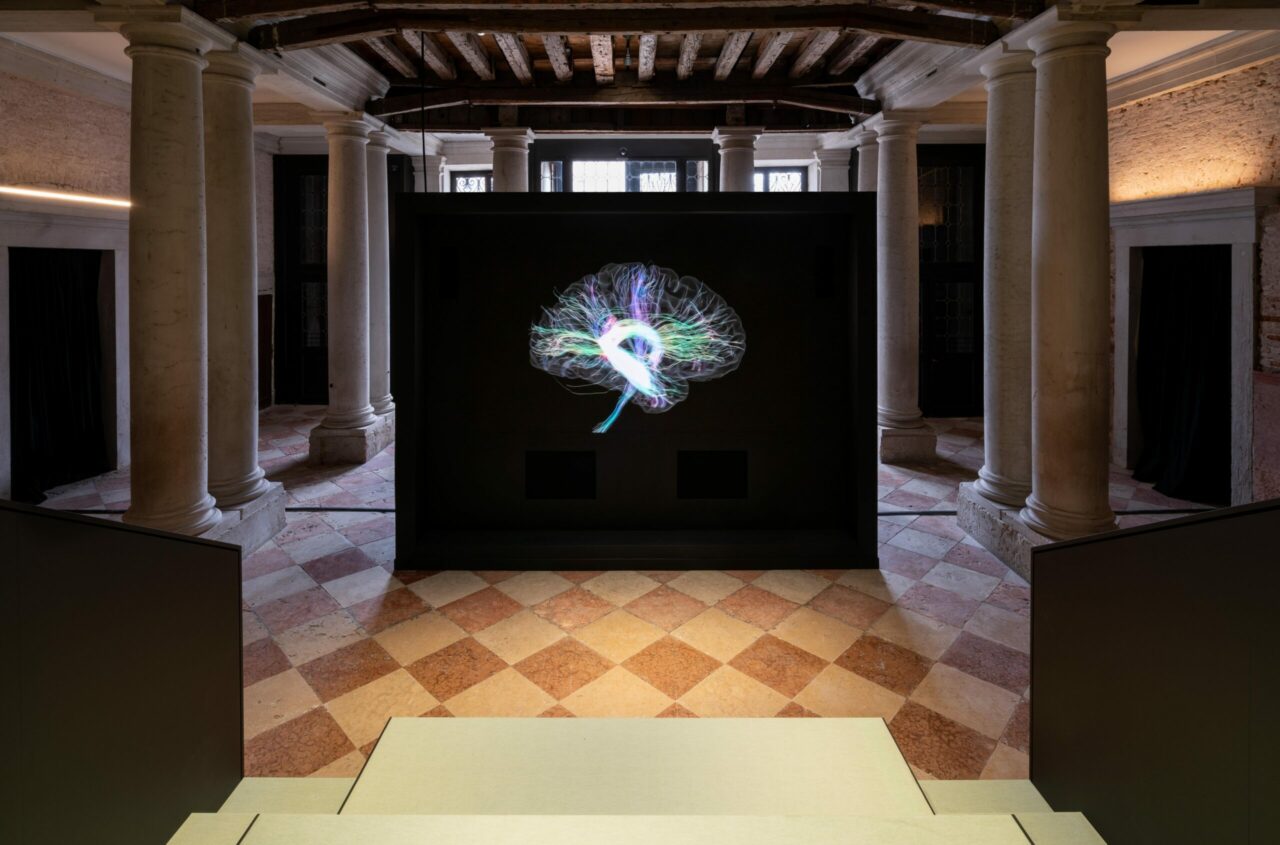

Exhibition view of “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” Fondazione Prada, Venice 23 April – 27 November 2022 Photo: Marco Cappelletti Courtesy: Fondazione Prada

Hardly any other human organ leaves so many scientific questions unanswered as the brain. Neurologists all over the world are trying to find out how it works and how it influences our actions and thoughts. The current research is only the latest form of a project that is as old as humanity and varies according to the prevailing scientific and ideological paradigms.

The Fondazione Prada in Venice is currently attempting to provide an overview of this project with the exhibition “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” in the Palazzo Ca’ Corner della Regina – on occasion of the Venice Art Biennale. The exhibition was curated by Udo Kittelmann in collaboration with the artist Taryn Simon, accompanied by an international advisory board of experts in the field of neuroscience. The core question of the exhibition, which extends over three floors of the Palazzo, is: What is the significance of the human brain, in all its functional complexity, for human history?

The exhibition not only presents medical information about the brain, but also displays over 110 objects that mark some of the most important stages of a millennia-long journey of discovery. Furthermore, 32 authors from all over the world have been invited to write fictional stories inspired by current scientific findings about human neurology. Another highlight of the exhibition is Taryn Simon’s “Conversation Machine”, in which thirty-six neuroscientists, psychologists, neurolinguists and philosophers interpret neuroscientific experiments and their philosophical implications on thirty-two screens in a random but curated dialogue.

The whole exhibition demonstrates par excellence the spirit of the new cultural shift – Culture Shifts Magazine is pleased to have met curator Udo Kittelmann in Venice for a conversation about the exhibition.

Culture Shifts: Mr Kittelmann, to begin with a question about the title of the exhibition “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea.” What is this idea and how did the idea for this exhibition come about?

Udo Kittelmann: The idea is certainly first of all that every thought must be given a form. Every thought first remains in an abstract space before it can be expressed verbally. But this always requires the imagination, the idea. The interesting thing is when you look at the human-historical dimension of the exploration of the brain: The Egyptians did not yet have any idea of the brain in our sense, but they had an idea that something higher actually guides us and located it in the heart. On the other hand, there is this wonderful depiction by Rembrandt in the exhibition in which the top of the skull is opened to take out the pineal gland, because in Rembrandt’s time it was believed that the soul was there ….. But first we have these two Sumerian clay scrolls, which are demonstrably one of the first inscriptions in human history of the idea of the dream. Such thoughts have fundamentally influenced human thinking about the brain.

CS: The exhibition starts with these first articulations of a concept of dream. In general, it places a strong emphasis on interaction and communication. It emphasises how much what we experience or communicate to each other is always a reaction to something that precedes it. How do you present this in the exhibition?

UK: The most important question we asked ourselves was: how do you transform our knowledge into an exhibition that is hopefully not didactic? There are books that show in a wonderful manner what happened in the 20th century, but something like that would remain purely illustrative. It would not make clear what difficulties lie in the matter. On the other hand, in conversations with the neuroscientists involved, one learns very quickly that we still know relatively little about the brain, about consciousness formation, about memory – and about how it works in general. It was a long journey of research to find objects that could be used to illustrate this – and to back it up with facts. And if you take the time to listen to the 36 scientists in the Conversation Machine for more than an hour, who only express short ideas that are then further thought out by another scientist, then you learn a lot. The idea was always to make the researchers the stars of this project, to take them out of the cocoon in which they are trapped and present them in a new context.

Exhibition view of “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” Fondazione Prada, Venice 23 April – 27 November 2022 Photo: Marco Cappelletti Courtesy: Fondazione Prada The Conversation Machine. Videos, interviews and orchestration by Taryn Simon. Produced by Fondazione Prada for the “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” project.

CS: Turning scientists – people who deal with the world and try to find solutions – into stars. How do they perceive this? Are they happy to be given such a stage in this context?

UK: Yes, like every person with a healthy egoism, I guess. But of course they are also grateful. We can observe this in television programmes, in film documentaries in recent decades, that more and more scientists are raising their voices. And that also meets tremendous interest. It would be good, and that is certainly one of the aims of this exhibition, to bring these things together with other fields of knowledge. This needs pragmatism on the one hand, but it also needs the form of a pragmatic way of understanding how people feel and think. And then, of course, different sciences belong together.

"The idea was always to make the researchers the stars of this project."

CS: That was new for you, that in this case you not only worked with artists or creative people in the conventional sense, but also with a different kind of actors.

UK: If we always spin around in the same circle of what we do professionally and don’t share with other people of a different kind, then it all remains inside a very narrow space. I believe that it is good for every science, it is good for everyone in humanities, it is good for every way of thinking to exchange ideas. It was always clear from the beginning that this kind of exhibition had never existed in this form before. It is also decidedly not designated as an art exhibition. Despite its positioning at an art biennial. There have been exhibitions in the recent past that have included art in the traditional sense as illustration. But we spoke out against that early on. On the other hand, there are exhibitions about the brain that work in a very technical spirit, but not in the same form as our project does. That was white land, unknown land, and that’s why it took endless meetings and endless conversations, almost exclusively about Zoom.

Exhibition view of “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” Fondazione Prada, Venice 23 April – 27 November 2022 Photo: Marco Cappelletti Courtesy: Fondazione Prada. Cylinders of Gudea Iraq, c. 2120 – 2110 BCE, terracotta Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités Orientales, Paris Exhibition copy

CS: Your exhibition has presented the history of the human brain as a cultural history. Was this a difficult approach?

UK: A major challenge was, of course, that the neurosciences are primarily a European and American field. And even scientists from Asia or Africa have often enjoyed their training at US universities and hospitals and have continued to be appointed there. It was exciting for us to make this as diverse as possible; the research also took us to South America and Asia to bring these materials together. On the other hand, there was this very nice idea of inviting 32 authors from all over the world – from Salman Rushdie to Esther Freud and from Daniel Kehlmann to Katie Kitamura – to write narratives and stories based on scientific findings in order to generate a surplus of cultural value.

CS: Times have changed. The world is in a miserable state. And the attention span of people within that state is very short. What was the motivation to make an exhibition that actually deals with the brain in a serious way, challenging the brain of the recipients in such a way that they can’t go through it in a few minutes – that they might even have to make an effort.

UK: When we started, there was neither the pandemic nor the whole warlike upheaval in Ukraine. I have to say it so frankly: would we do it again today in the same way or would we have to turn to another topic? But it is the brain that organises all this. The brain, thinking, memory, consciousness is what makes the world we live in the way it is. Otherwise it would perhaps all look different. And when you walk through these three floors, past 110 objects, in this dark labyrinth … see the showcases, the objects, listen to the stories, and then at the very top experience the so-called Conversation Machine by Taryn Simon, in which a total of 36 scientists are in a debate for over two hours, in a constant exchange of their ideas, then it becomes very clear: thinking is exhausting. Thinking is incredibly complex. Yet the world we live in is trying to do just the opposite: to break down complexity into simple elements. But that is certainly not how the brain works. It is much more complex than any simple structure can ever represent.

Hieronymus Bosch The Extraction of the Stone of Madness, c. 1501–1505 oil on oak panel Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, inv. no. P002056 © Photographic Archive Museo Nacional del Prado.

J.W. Belliveau et al. “Functional Mapping of the Human Visual Cortex by Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Science, vol. 254, n. 5032 American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, 1991 Illustration courtesy of Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

CS: Is there a new paradigm waiting for us – one that will perhaps be strongly determined by a new kind of technology? How do you think we will think in a few decades?

UK: If the question were to be asked about how the human brain is changing towards a conceivable future, all I can say in response is: for one thing, it takes a very, very long time. It can’t be transformed so quickly. It may also take generations. In different cultural circles, different developments will take place, due to different socialisations and experiences. On the other hand, I do believe that the brain and its thought process can be shaped more creatively in the not too distant future, if we know more about it and its functions. How can that be done? I am still a layman, after those two years. I don’t know how it will change. I can only keep saying: hopefully for the better. We will see …

"You can't feel your brain."

CS: Mr Kittelmann, how does your own brain actually look after this exhibition? Do you look at it with different eyes now?

UK: One of the perhaps more important things that I learned – especially in the final phase of the project – and which I was never aware of before, is: you can’t feel your brain. (When we talk about headaches, it has nothing at all to do with our brain mass, with the brain as an organ.) We can actually feel all the organs. But nothing of what the brain does: not our motor function, not our speech. Nothing we can feel. It is, if you like, an insensate thing. And yet it is the thing through which we construct the world for ourselves.

The exhibition will be open until November 27th 2022 at Fondazione Prada Venice.